How to Improve Your Two-Mile Run

A plan to improve a two-mile run is probably our most-requested bit of training content. Truthfully, I think I’ve put this off due to the fact that the way I’d go about doing it with an athlete felt too simple…too obvious. “Surely if I were to write this down,” I told myself, “people would complain that it’s not complicated enough.” After fighting through the throes of imposter syndrome, I’ve decided “screw it, let’s give the people what they want.”

So, here we are: a straightforward guide on how to improve your two-mile run.

Before we begin, a bit of clarification.

What This Article Is

My intent here is to provide a very straightforward 8-week path detailing how I would improve an athlete’s two-mile run time. The 8-week timeline is a bit arbitrary - you could easily do this in less time, just as you could obviously take much longer if that’s an option for you. The decision becomes one of trade-offs: shrinking the timeline increases the demands on the athlete, just as lengthening the timeline increases the demands on the logistics.

What This Article Is NOT

This is not complicated. To be clear, endurance literature (probably more so than strength literature) prides itself on taking an overtly complex approach to its trade secrets. We’re not going to get into blood lactate, aerobic thresholds, complicated pacing structures, etc. These tools absolutely have a place, and at the highest levels, they’re pretty essential. But for the majority of athletes out there, coached or self-coached, a simple approach is best.

The Context

Let’s set the scene. You’ve just completed a PT test, and your two-mile run was slower than you wanted it to be. For the purposes of this article, let’s say you ran an 18:00 two-mile and in a few months’ time you want that to be somewhere closer to 16:00 (or faster). The facts of the case are these:

Current Time: 18:00 two-mile

Current Pace: 9:00/mile

Goal Time: 16:00 two-mile

Goal Pace: 8:00/mile

Dropping two minutes off our run, in this example, represents a 12.5% improvement. In my mind, this is very achievable in 8 weeks. The “percent improvement” is probably my first question mark when it comes to determining how much time I’d expect an athlete to need to improve performance. If we were looking at a 20-25% (or more) improvement, we’d need more time.

The Approach

To keep things super simple, I’m going to lift and separate the entirety of this training plan from the intricacies of a “true” hybrid set up…one in which I’d be factoring in strength, work capacity, etc., alongside the run work. I’ll make some comments on what that combination might look like towards the end of the article for the sake of clarity.

At any rate, a training model that will work for 99% of athletes 99% of the time is to set aside three days per week of dedicated run work. The specific layout will be as follows:

Day 1: Intervals/Speed Work - paces that are faster than our goal pace of 8:00/mile

Why? Overspeed work helps the body adapt to a faster pace. It also “builds specific strength” in the running sense

Day 2: Tempo/Threshold Work - paces that “comfortably hard,” juuust slower than our goal 8:00/mile pace

Why? Flirting with paces right around goal pace, and distances right around goal distance, acclimate the body to what we’re actually trying to do: run 2 miles

Day 3: Long Run - easy, nose-breathing-type stuff. I’m not worried about pace here, just volume

Why? Durability, for one. But also from a physiological standpoint, this is the boring-but-magical work that increases our aerobic base and the bank of oxygen that we’re able to draw from

Two quick comments. First, if you’ve read any of my work, you’ll know that I’m a fan of “consolidating stressors,” which basically means transitioning from high intensity/low volume early in the week towards low intensity/high volume later in the week. This three-day setup maps to that more complicated hybrid setup quite nicely. Second, I would recommend spacing these run-specific days out by at least one training day. It gives the body time to rest, and also allows us to inject additional stimuli into the training plan (strength, work capacity, etc.). With all that being said, here’s what we’re looking at off the cuff:

I’ve spaced these out by a day with the exception of the long run. From a logistical standpoint I find that most folks have more time to train on the weekend. Thus, our long run falls on the weekend. If your situation is different, adjust your training schedule.

The Sessions

With our three session types in mind, the next logical question would be “great, so what do they actually look like?” I’m glad you asked.

Before we dive into it, though, I want to acknowledge a very important fork in the road. It is here, in determining session types, that we make a choice between “complexity” and “simplicity.” As I stated earlier, I am partial to the “simple” path and, thus, this will be the path we take. For a more complex approach to endurance session design, I’d point you towards an actual endurance resource/coach.

Session 1: Intervals/Speed Work

Since we’re working off a 2-mile goal distance, our intervals will consist of shorter, faster distances. 400m, 600m, 800m repeats, etc. If our athlete needs to prioritize pure speed, we’ll bias towards the shorter stuff. If their speed is there, but we need to have them sustain it for longer, we’ll bias towards the longer stuff. Also, because these are intervals, we need to think about the duration of rest between each. With speed and technique being the priority, we will typically allow for a rest bout that is longer than the preceding work bout. For example, if a 400m interval takes us 2:00, we might rest for 3-4 minutes before going again.

Summary: 200m-800m with a 1:2-3 work:rest ratio

Session 2: Tempo/Threshold Work

This type of work gets tricky. On the one hand, we can stay ultra-simple and just have the athlete run their race distance at a pace that is slightly slower than goal pace. On the other hand, we can go back to the interval set up but choose repeated distances that are closer to our race distance than our pure interval days. These would be executed at a pace that is faster than our goal pace. An example might be 1000-1200m repeats. Because we’re pushing more of a tempo/threshold stimulus, our rest intervals are going to be roughly equal to our work intervals. Over time, we might shrink that rest period to promote a bit more fatigue resistance.

Summary: 1000-1200m repeats with a 1:1 work:rest ratio OR 2-mile efforts

Session 3: Long Run

This is what it sounds like: a long run. I mentioned earlier that pace isn’t an issue here, and that holds true so long as the athlete is running slow enough to actually get the stimulus we’re after. This is where you so often hear the phrase “Zone 2,” but we’re not going to get into that because we’re focusing on simple. My guidance is to settle into a pace that allows you to breathe through your nose. Another way of thinking about it is that you want to run at a pace that allows you to just barely hold a conversation at a normal cadence. If you feel like it’s too slow, then you’re probably at the right pace.

Summary: 1.5-2x race distance (or longer) at a slow, easy, sustainable pace

The Progressions

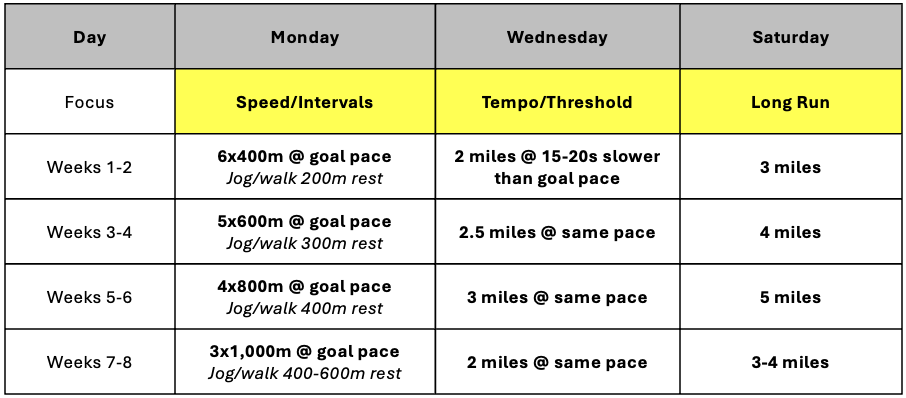

Finally. What you’re all here for. “Lovely,” you say, “we have all these session types. Now, how do we progress them across eight weeks of training?” I’ll give you the chart first, then I’ll walk through the explanation behind it.

The first thing that stands out is that we’re keeping our sessions fixed for two weeks in a row. I like this a lot because it gives the athlete the chance to take lessons learned from one week and carry them into the next. For a new or inexperienced runner, first exposures can be a scary thing. Gaining an understanding of pacing, session strategy, etc., is incredibly valuable and can pay dividends in the week following. This reality is often overlooked for the sake of “changing things just to change things.” Remember: simplicity.

The other thing to notice is that this approach follows a kind of natural increase in both volume and intensity over time. On the intervals, for example, we’re keeping our pace fixed across all eight weeks, but we’re slowly increasing the duration of the intervals. This will challenge the athlete to maintain that goal pace across ever-increasing distances. Similarly with the threshold runs: we’re going slower than goal pace, but the distances are increasing as well.

All of this training, when combined, is intentionally building up fatigue. The truth is that this fatigue builds up, across time, and will actually mask some of our performance gains. As we draw volume down slightly towards the tail end of our eight-week phase, those performance gains will become more and more apparent, eventually culminating in an increased performance on game day.

A Quick Note on the “Other Stuff”

I mentioned earlier that I’d touch on the hybrid training stuff. I’m aware that if ever this article were to get too complicated, it would be here. So I’ll keep this intentionally brief. The reality is that our athlete won’t just be doing run days. They’ll also be lifting, doing work capacity, etc. With that being the case, I’d organize my sessions across the week in accordance with the Consolidation of Stressors concept I mentioned earlier. At the front end of the week, around my interval sessions, I’d inject my heavier (higher intensity) lower body work so that the body is experiencing the same type of fatigue across clustered days. As we move across the week towards the longer run, I’d be injecting my higher-volume work capacity sessions as well as my upper body sessions so that we conserve as much “adaptation currency” as possible for the higher-volume endurance efforts. I’ll dive into the complexities of that setup in a different post.

Closing Thoughts

There you have it. An incredibly simple and straightforward way of improving your two-mile run performance in eight weeks. Could we make this more complicated? Sure. Will other coaches tell you to do this differently? Undoubtedly. But, and perhaps most importantly, will this work? Yes. Absolutely.