You Are the Experiment

Training Like an N of 1

This is a guest blog post submitted by a member of Leg Tuck Nation. The content represents their own views and opinions, with edits made only for grammar, clarity, etc. If you are interested in submitting your own content for consideration, click here.

We live in the age of evidence-based everything. Whether it’s lifting protocols, nutrition guidelines, or recovery modalities, we’re constantly told what “the science says.” And while research is an invaluable tool, here’s the uncomfortable truth: no one is the average of all people.

In strength and conditioning, most studies present highly controlled environments, measuring outcomes based on group averages, standard deviations, and outliers trimmed off the edges. But you’re not average. You’re you. Your body, your job, your stress load, your sleep rhythm, your digestion, your past injuries. All of it matters. That’s why it's critical to start treating your training and nutrition like an “N of 1” experiment, where the subject that matters is you.

Science Informs, You Refine

To be clear, good science is your launchpad. Peer-reviewed literature and proven methods helps us filter out nonsense and gives us a foundation rooted in physiology and decades of accumulated knowledge. But applying those general rules to an individual requires testing, adjusting, and tracking.

Maybe you are told 8 hours of sleep is non-negotiable. But you wake up at 0430 every day for shift work, and after five hours, you feel sharper than most people are at noon. Should you write this off? Maybe not.

Roughly 1–3% of the population carries a rare gene mutation that enables them to sleep only 4–5 hours per night without cognitive or physiological decline. These people aren’t “hustle culture” enthusiasts, they’re genetically wired for it. But unless you test and track your own performance, you won’t know if you’re part of the 3% or simply under recovered and lying to yourself (Pandey, Pritika et al 2023).

Here’s another perfect illustration of variability: not everyone responds the same way to steady-state aerobic training.

In classic aerobic protocols (moderate-intensity continuous training), researchers have observed non-responders, people whose VO2 max or cardiovascular metrics barely budge despite adherence to the program. Some argue that “non-response” is a myth, suggesting that by adjusting dose or intensity, you can overcome it. But the phenomenon still forces us to confront individual variability.

The interesting thing is that many of those “non-responders” to moderate aerobic work do respond when switched to HIIT. In fact, a number of studies show that HIIT protocols often generate higher responder rates for VO2 max or cardiovascular gains compared to moderate continuous training. In one study, nearly all participants responded to HIIT, while a sizable fraction showed no significant change under moderate training (Mattioni Maturana, Felipe et al. 2021)

Training as a Self-Study

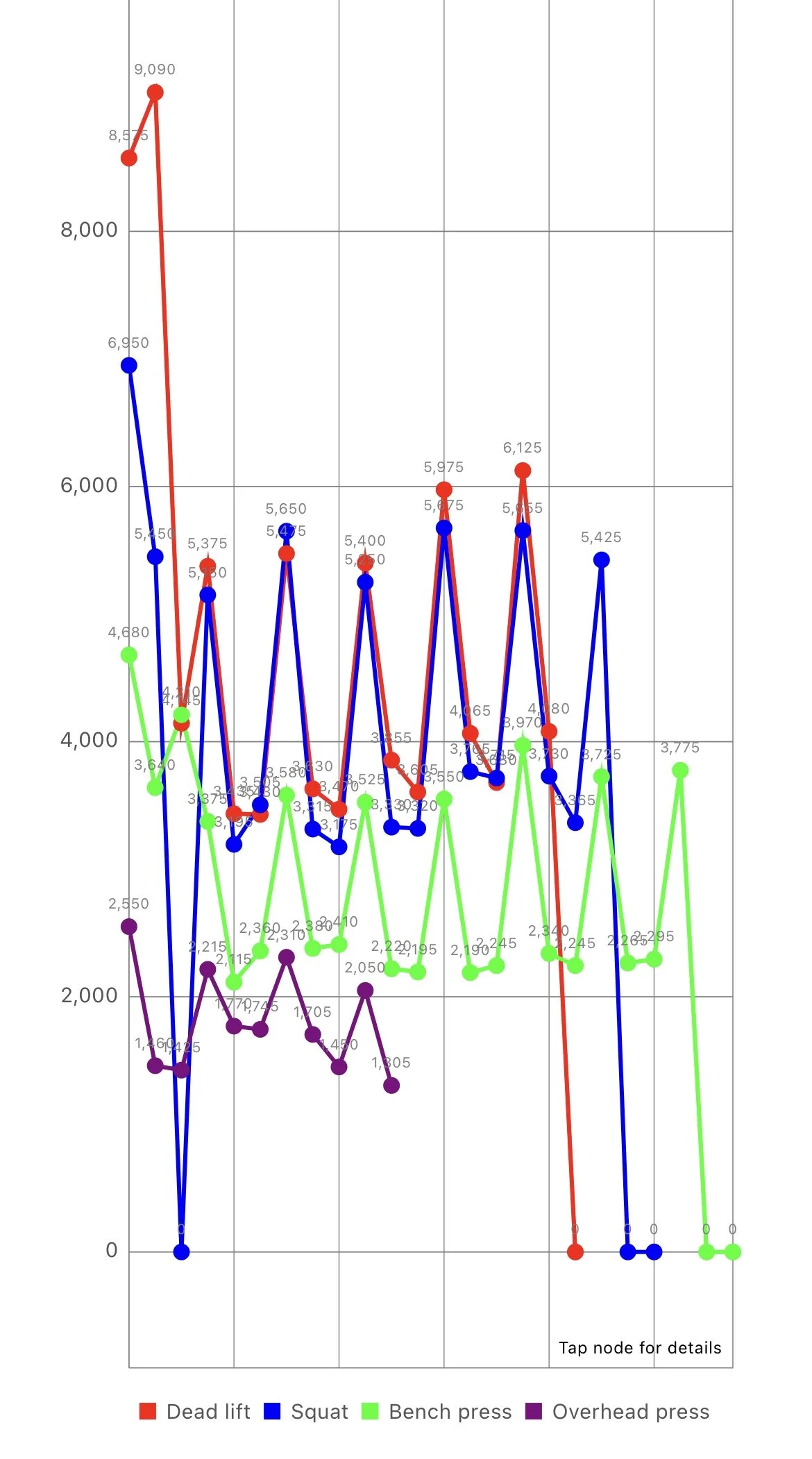

If you’re serious about long-term performance, you need to approach your programming with the mindset of a scientist. That means you establish a baseline, apply a method, and test the results.

Are you running a 6-week training block? Measure your lifts, your bodyweight, your sleep quantity and quality, and your mood at the start. Then retest at the end. If your bench stalled but your overhead press jumped by 15%, ask why. Were you more recovered for one? Was the volume a better fit? Was your sleep different? These aren't setbacks, they're data points.

Trying a new ruck protocol from the latest SFAS prep manual? Record your times, your load, your RPE, and how your knees feel the next day. You are the data set. Use it.

The Scientific Method Is Your Training Partner

A common truth is that most people fail to improve because they’re either doing random training or they’re blindly loyal to a system that doesn’t fit them. Applying the scientific method breaks that cycle.

Ask a Question – “What’s the least amount of strength training I can do and still gain?”

Form a Hypothesis – “I think 2 heavy sessions per week can improve my 1RM squat and bench.”

Test It – Execute the plan for 4–6 weeks.

Collect Data – weight lifted, soreness, progressions, overall feel, pre-workout meals, etc.

Evaluate – Did it work? Why or why not?

Adjust – Tweak volume, intensity, or recovery strategies based on the result.

Test, Don’t Guess

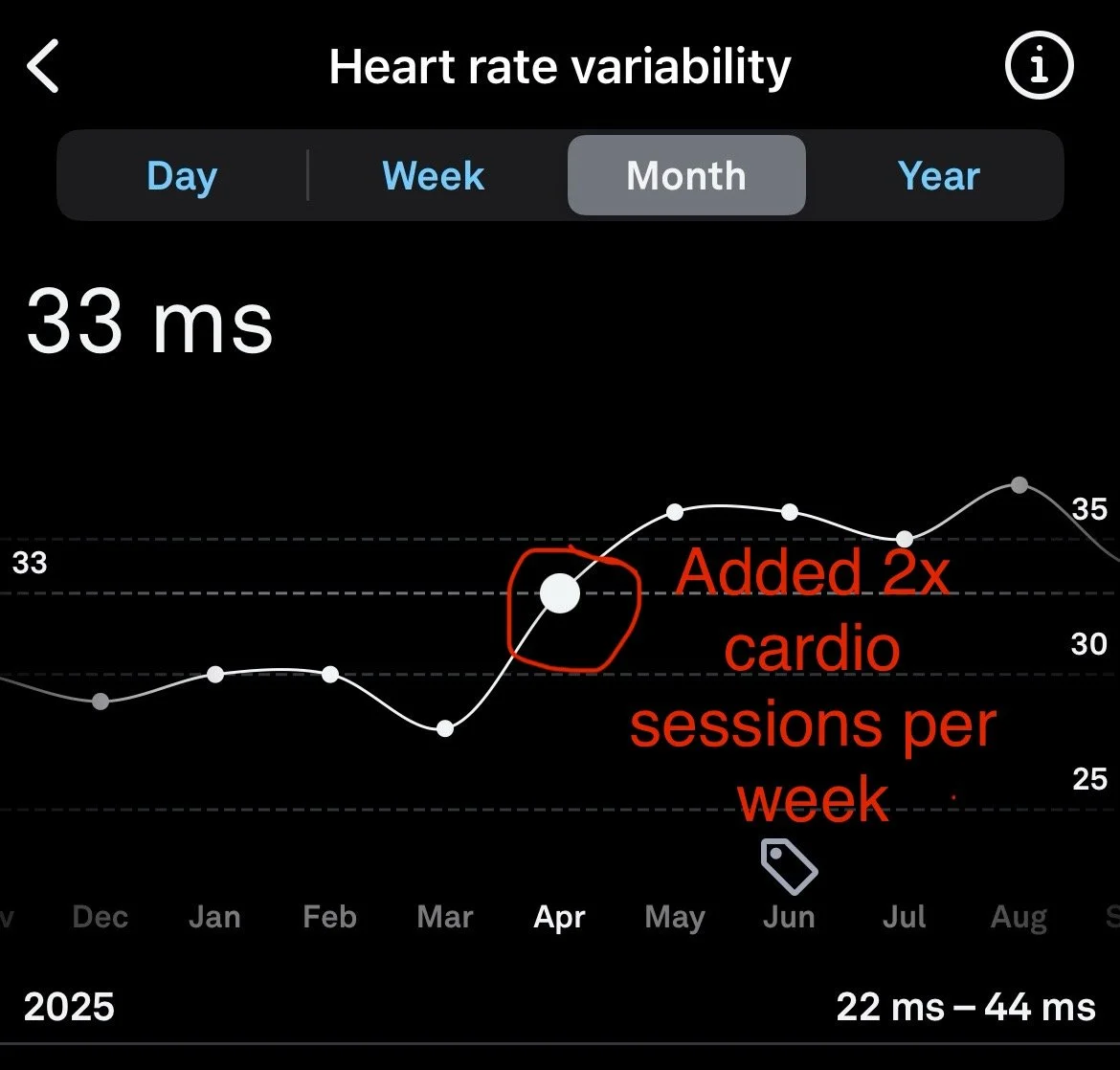

Periodic testing is the linchpin of all this. No coach should set a program without retests. If your goal is tactical readiness, hypertrophy, or endurance, test it. Know your numbers, your run splits, your ruck pace, you’re waking HRV. If it’s measurable, it’s improvable.

Think of it this way: if you’re not testing, you’re just exercising. If you’re testing, adjusting, and progressing, you’re training. If you’re doing Long and Strong, you can go back and see the periodic testing that was built in.

Take Ownership of The Process

There’s power in taking control of your own progress. It's not about ego lifting or perfection; it's about individual ownership. You don't need a PhD to notice when a new pre-sleep routine makes you feel better in the morning, or when higher rep deadlifts make your back angry. The self-awareness and data tracking you build will take you further than any cookie-cutter plan.

Sources

Pandey, Pritika et al. “A familial natural short sleep mutation promotes healthy aging and extends lifespan in Drosophila.” Research square rs.3.rs-2882949. 2 Jun. 2023, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37163058/

Mattioni Maturana, Felipe et al. “Responders and non-responders to aerobic exercise training: beyond the evaluation of V˙O2max.” Physiological reports vol. 9,16 (2021): e14951. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34409753/

Mark A. Christiani is a Tactical Strength, and Special Operations Army Veteran. He has human performance experience in the worksite wellness, collegiate and tactical settings. Mark holds a Master of Science in Sports Medicine from Georgia Southern University and several certifications, including CSCS and RSCC. Currently, he serves as an on-site Human Performance Specialist with the US Army Reserves. Mark's extensive background in research, coaching, and injury rehabilitation underscores his commitment to advancing the field of sports science and human performance.