Three Strategies for Functional Conditioning

We spend a lot of time at MOPs & MOEs preaching the benefits of increasing the amount of steady-state Zone 2 in your training. For all intents and purposes, the best approach to Zone 2 training involves monostructural movements done for extended periods of time…long bouts on the bike, multiple miles on your feet, etc.

But what if you’re looking to chase a similar steady-state feeling in the gym? Or put more plainly, what if you’re looking to mix things up a bit by combining multiple modalities into a conditioning-type session that is taxing but sustainable? The purpose of this article is to provide you with three quick strategies that you can implement right away to add an element of “functional conditioning” to your training sessions.

A NOTE ON SUSTAINABILITY

The concepts discussed below are all focused on creating a sustainable level of intensity within your gym-based conditioning, meaning that efforts are repeatable. This is not a primer on how to conduct high-intensity interval training.

INTERVALS

This approach expands a bit on the framework we laid out in our article on programming work capacity. By getting creative with your multi-modal interval structures, you can dial the intensity back, build in intentional rest breaks, and capitalize on your aerobic capabilities to elicit the stimuli we’re after.

Step 1: decide on a time domain. You can use our work capacity guidelines or come up with your own. For this example, we’ll say we want to complete three bouts of five minutes of work, for a total of fifteen minutes.

Step 2: decide on rest breaks. While a 1:1 work:rest ratio is the traditional “aerobic” prescription, we can dial that back a bit for the sake of time if needed. For our 3x5 minute example above, let’s put three minutes of rest between each effort. Our structure now looks like 3x5 minutes of work with 3 minutes rest between each.

Step 3: decide on movements. We dive a lot deeper into this in the work capacity article referenced above, but when it comes to movement selection within the construct of “functional conditioning,” I tend to stick to bodyweight (i.e. burpees), unilateral (i.e. DB lunges), and monostructural (i.e. C2 bike) movements. Because of the cumulative fatigue that can build up with this type of structure, it’s best to avoid bigger, heavier, more technical movements. Additionally, because the clock is running and we’re accumulating work, it’s best to avoid movements that require complex set up (i.e. unracking a bar from the rack every time).

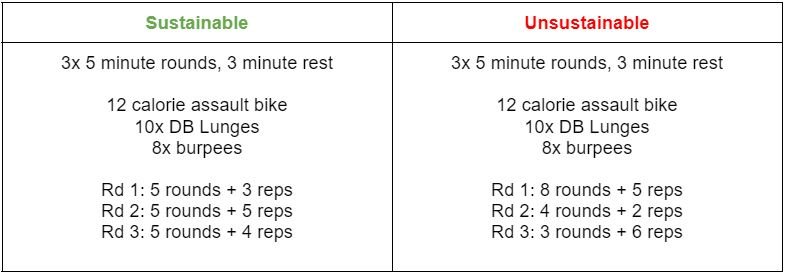

Step 4: stay repeatable! This is key. When you execute your first five minute bout of work, track the number of reps or rounds you complete. When you come back to the second round after your three minute rest break, the goal is to repeat (not exceed) that same amount of work. This is where functional conditioning really shines. If we go too hard and decrease the amount of work each block, that represents an unsustainable level of work and thus misses the purpose.

Sustainable work represented by the ability to repeat a roughly equal output each round

“TRIATHLONS”

No. Not swimming, biking, and then running…although that is a fantastic combination of events if you’re looking to create a robust aerobic system.

I use the term “triathlon” in this sense to describe a type of cyclical training where you rotate between several different machines/modalities to alleviate boredom and create enough novelty to get you through what might be an otherwise straightforward aerobic session.

A classic example of this setup might be as follows:

6-8 Rounds

500m Row

500m Ski Erg

400m Run

You can see right off the bat that across 6-8 rounds, a solid amount of aerobic volume will be completed. You should also be able to conceptualize how alternating between three different aerobic modalities might be a little bit more entertaining than sitting on the rower for an hour.

One important point here: the same sustainability rules from our Interval framework apply here. The goal each round would be to maintain the same pace on the rower, ski erg, and run. By default, this rule should force athletes to dial intensity back. If we see the pace slow down, we have violated the sustainability principle and have entered into the realm of unsustainable intensity training (HIIT).

These types of sessions may require a bit of pre-planning, as depending on the layout of your training space and the types of equipment you have access to, stacking multiple cardio machines might be logistically impossible. I’ll point out that although I call this approach a Triathlon, you can accomplish the same objective using less than or even more than three pieces of equipment. Get creative!

ISOMETRICS

The definition of an isometric movement is a movement in which the length of the muscle remains static, i.e. the muscle doesn’t move. Some straightforward examples include static hangs from a pull up bar, ring planks, kettlebell front rack holds, or even farmer’s carries (although you are moving, the hold itself could be considered isometric).

So how does this factor into our functional conditioning framework? By injecting isometrics into our gym-based conditioning, we can trick the athlete into slowing down without deliberately telling them to. Let’s compare two prescriptions:

Note the inclusion of isometric-type exercises in red

Without any additional context, the prescription on the left promotes high intensity. The athlete is given three movements and told to complete as many rounds as possible (AMRAP) within the 12-minute time cap. Despite your best efforts to coach the athlete into slowing down and staying sustainable, no constraints have been introduced to actually entice them to do so.

The prescription on the right, however, introduces two examples of isometric movements that will all but require the athlete to slow down, control their breathing, and decrease their level of intensity to something more sustainable/repeatable. Regardless of how hard they want to work, a full minute of each circuit will be dedicated towards staying still and, effectively, recovering.

I like this approach for two reasons. First, some athletes you work with will be all gas and no brakes. Regardless of what you try to tell them, they’ll come out of the gate hot and try to maintain that for the duration of the prescription. By introducing isometrics, you can still have them under the assumption that they’re “hitting a hard metcon” without actually destroying themselves. Call it a trick of the trade.

The second reason I like this approach is that it’s easy to dial up and down based on how much you want to adjust the intensity. Adding more isometrics will lower the intensity and increase the sustainability, whereas decreasing the number of isometrics will increase the intensity and decrease the sustainability.

CLOSING THOUGHTS

Functional conditioning is the Pandora’s Box of gym training. I have seen coaches and athletes throw anything and everything in the hat and label it gym-based conditioning with no real thought towards what stimuli they’re trying to achieve or how to even structure these types of sessions. While there are arguably more than three tools that you can use to help guide your programming, hopefully the ones listed here are at least helpful in pointing you in the right direction. The key is to create prescriptions that promote sustainability and repeatability of effort, as that is ultimately the purpose of aerobically-biased gym work in the first place. Once that foundational principle is in place, the world is your oyster.